Climate

Solar radiation by the Earth's surface and atmosphere is key to the climate of the Sahtu. The strength of this radiation is determined primarily by latitude. Snow cover, clouds and large variation in hours of daylight and sun elevation during the year are also factors.

The heat of the sun is constantly redistributed between regions by air circulation. In the winter, the Sahtu is dominated by air flowing from the polar region. The Mackenzie Mountains protect this air mass from milder, moist Pacific air. The low sun angles ensure low solar input.

In general, the Sahtu has long, cold winters and relatively short, cool summers. The average temperature in January ranges from -20º C to -30º C, while the average temperature in July ranges from 10º C to 15º C. Annual precipitation varies from 200 mm in the barrenlands to 700 mm in the mountains. The summer and winter cycle is very pronounced and is separated by spring break-up and autumn freeze-up.

In the summer, the air circulation pattern alters. Artic air recedes, allowing low pressure cells to gain access from the southwest. Along with this change, the air flow from the south combine with the long hours of sunlight make the Sahtu, especially in the Mackenzie Valley, the warmest for its latitude in all of Canada.

Temperature inversion, when the cooling of air temperature with altitude is reversed, is a common phenomenon in the Mackenzie Valley. Inversions in Norman Wells can result in air temperatures at the top of the Franklin Mountains (approx. 1000 m) 10 degrees warmer than at ground level.

Precipitation in the Sahtu is restricted partly because of the rainshadow effect of the Mackenzie Mountains. Average precipitation throughout the Sahtu is 300-400 mm annually. Precipitation decreases at the more northern latitudes, tapering off to 250 mm at the northern boundary.

Low pressure systems enter the Sahtu, typically from two major routes. Air flow originating in the northern Pacific Ocean moves through the Alaskan valleys into the Yukon and then into the Mackenzie Valley, proceeding south. Air moving directly south from the Beaufort Sea mixes with this Pacific flow to form the primary pathway.

The second air mass flows from south in the Pacific Ocean through various breaks in the Cordillera and finally moving north through the Liard Valley or along the Taiga Plains further east.

Daily rainfall is typically light with few days exceeding 5 mm. Heavy daily rains from localized storms in the summer can exceed 50 mm.

By November, precipitation primarily falls as snow. Mean monthly snowfall rises sharply and then diminishes through the winter months as the artic high stabilizes and prevents humid air from the Pacific from moving in. Even as snowfall decreases, snow accumulation steadily increases throughout the winter due to lack of any significant thaws. Maximum snowpack depth is reached in March. Amore rapid decrease in the snowpack then occurs over the spring season.

© Robert Kershaw, 2004

Early winter ice forming along Great Bear Lake shoreline

Permafrost

The Sahtu lies entirely within the permafrost region of northwestern Canada. The temperature of the ground is continuously below 0º C over significant proportions of the area. Therefore most moisture in the ground occurs as ground ice. This ground ice occurs in many forms, most often as fillings in the pores of soils; however, it can also form much more massive bodies, such as ice wedges and layers up to several metres thick. The ground surface undergoes annual deep seasonal thawing and freezing with summer's heat and extreme winter cold. Both the presence of ground ice and surface thaws and freezes have major effects on the landscape on roads, construction and development in the Sahtu.

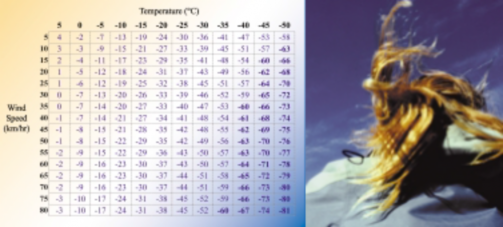

Windchill

What is wind chill?

Wind Chill is the cooling sensation caused by the combined effect of temperature and wind. Our bodies insulate us somewhat from the outside temperature by warming up a thin layer of air close to our skin. When the wind blows, this protective layer is taken away. Energy is needed for our bodies to warm up a new layer. If each layer keeps getting blown away, our skin temperature will drop. Wind also makes you feel colder by evaporating moisture on your skin, drawing more heat away from your body.

In parts of the country with a milder climate, a wind chill warning is issued at -35° C. Most of Canada hears a warning at about –45° C. Residents of the arctic regions have grown more accustomed to cold, severe conditions and are warned at about –50° C.

Where is the coldest wind chill in Canada?

The coldest wind chill on record occurred at Kugaaruk (formerly Pelly Bay), Nunavut, on January 13, 1975. The air temperature was -51°C, and the 56 km/h winds produced a wind chill of -78° C.

The above table shows the relative drop in temperature at varying wind speeds.

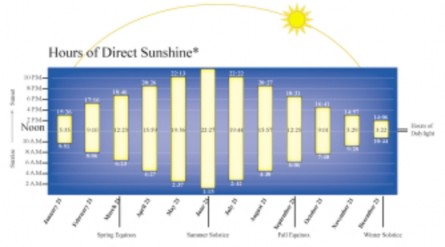

Land Of Light

Sunrise and sunset conventionally refer to the times when the upper edge of the disk of the sun is on the horizon, considered unobstructed relative to the location of interest. Atmospheric conditions are assumed to be average, and the location is assumed to be in a level region on the Earth's surface.

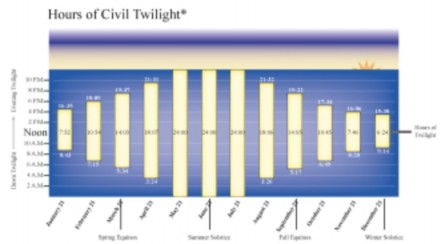

Civil twilight is defined to begin in the morning and end in the evening, when the center of the sun is geometrically 6 degrees below the horizon. This is the limit at which twilight illumination is sufficient, under good weather conditions, for terrestrial objects to be clearly distinguished; at the beginning of morning civil twilight, or end of evening civil twilight, the horizon is clearly defined and the brightest stars are visible under good atmospheric conditions, in the absence of moonlight or other illumination.

In the morning, before the beginning of civil twilight and in the evening, after the end of civil twilight, artificial illumination is normally required to carry on ordinary outdoor activities. Complete darkness, however, ends sometime prior to the beginning of morning civil twilight and begins sometime after the end of evening civil twilight.

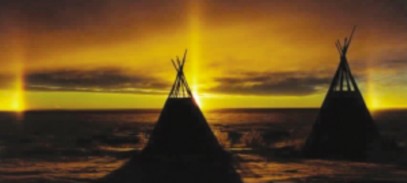

Sun dogs, also called mock suns or "parhelia", are colored, luminous spots caused by the refraction of light by ice crystals in the atmosphere. These bright spots form at points on the solar halo, 22 degrees on either side of the sun and at the same elevation.

Sundogs are visible when the sun is near the horizon (therefore seen during the winter months) and on the same horizontal plane as the observer and the ice crystals. As sunlight passes through the ice crystals, it is bent by 22 degrees before reaching our eyes. This bending of light results in the formation of a sundog.

The difference between sundogs and sun halos is the result of the orientations of the ice crystals. If the sun passes through the hexagonal crystals when their flat faces are horizontal a sundog is observed. If the hexagonal crystals are randomly oriented, a halo is observed.

Sundogs over Great Bear Lake

photo by Morris Neyelle, Deline

Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, are distributed along a narrow band encircling the North Pole. The Sahtu lies within the auroral zone, in which the Lights are most often seen.

The Aurora Borealis is an electrical discharge powered by a "generator" composed of the solar ‘plasma particle’ wind and the earths magnetosphere.

As the solar wind blows towards the earth from the sun, a cavity known as the magnetosphere is formed when the plasma meets an invisible obstacle of the earth's magnetic field. The earth's magnetic lines above the polar region fan out and connect to the solar wind's magnetic lines at the magnetosphere's boundary. The solar wind blows around this boundary across the connected field lines, generating power up to 1,000 billion watts. When this current of (mostly) electrons collides with atoms and molecules in the upper atmosphere, they emit the characteristic northern lights. The whole process is comparable to neon lighting.

(Adapted from the GNWT Resource Wildlife and Economic Development: www.gov.nt.ca/RWED/

Aurora Borealis

Temperature

In general, the Sahtu has long, cold winters and relatively short, cool summers. The average temperature in January ranges from -20º C to -30º C, while the average temperature in July ranges from +10º C to +15º C. Annual precipitation varies from 200mm in the barrenlands to 700mm in the mountains.

Mean monthly temperatures tend to be relatively uniform, however there are regional variations. Temperature inversions, when the cooling of air temperature with altitude is reversed, is a common winter phenomenon in the Mackenzie Valley. Inversions in Norman Wells can result in air temperatures at the top of the Franklin Mountains (approx. 1000 m) 10 degrees C warmer than at ground level. The area surrounding Great Bear Lake is cooler in the summer than the Mackenzie Valley. The lake’s large water body, whose temperature rarely exceeds 5°C, creates a cooling effect on the surrounding air mass. Throughout the 20th century, mean annual temperatures for most recording stations in the Sahtu have on average risen between 1 and 2 degrees Celsius.

Fall can turn to winter quickly. In two days, ice has begun to form in Keith Arm on Great Bear Lake.

© Robert Kershaw, 2002

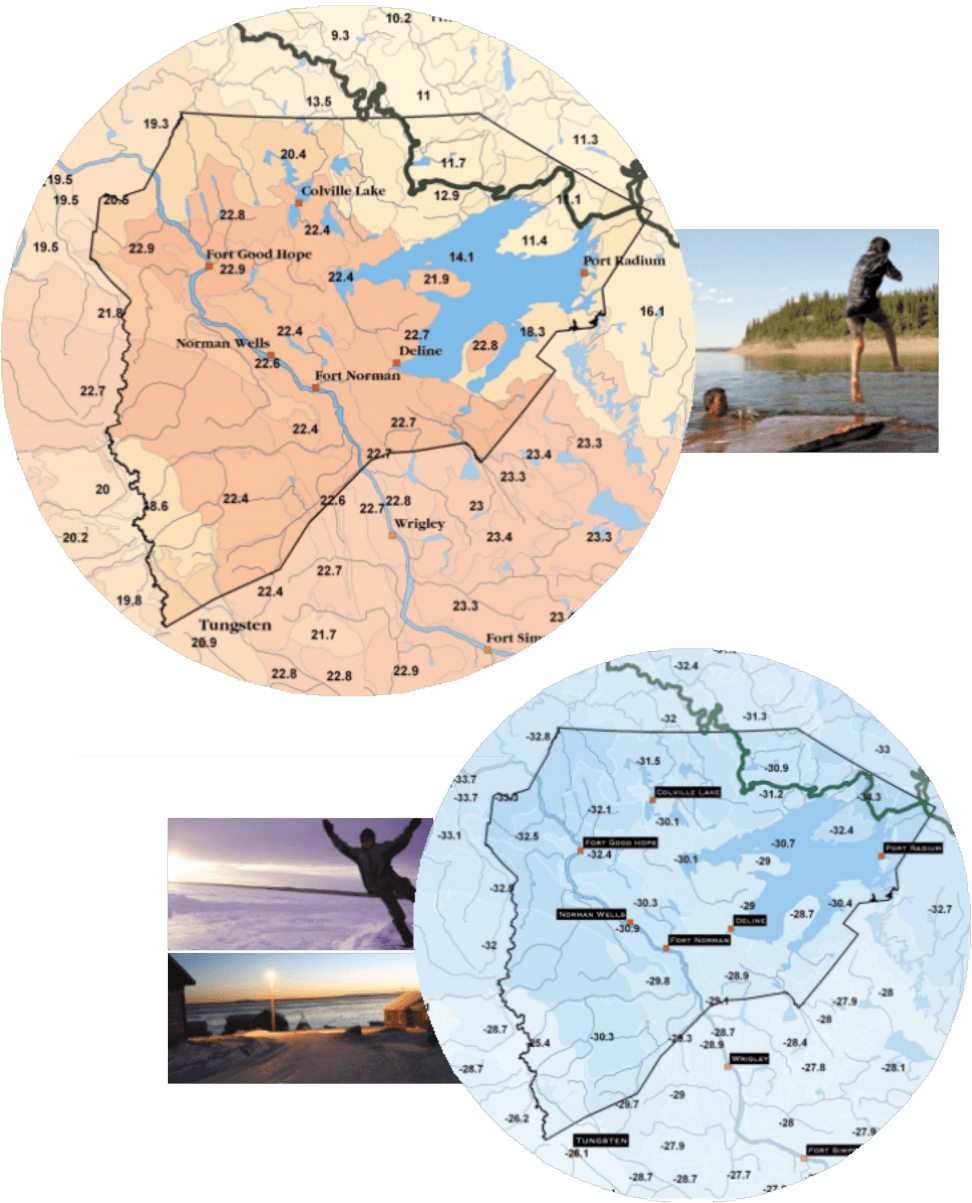

This model estimates the mean daily temperature of each ecozone based on an interpretation of data collected from weather stations in the region. The maximum and minimum temperatures of each day at each weather station are averaged to obtain the mean daily temperature. The mean daily temperatures are then averaged over a 30-year period (where available) for every day of the year.

In The Dog Days Of Summer

Summer Temperatures

Estimated average daily high temperature in July.

..And in the darkness of winter

Estimated average daily high temperature in February.

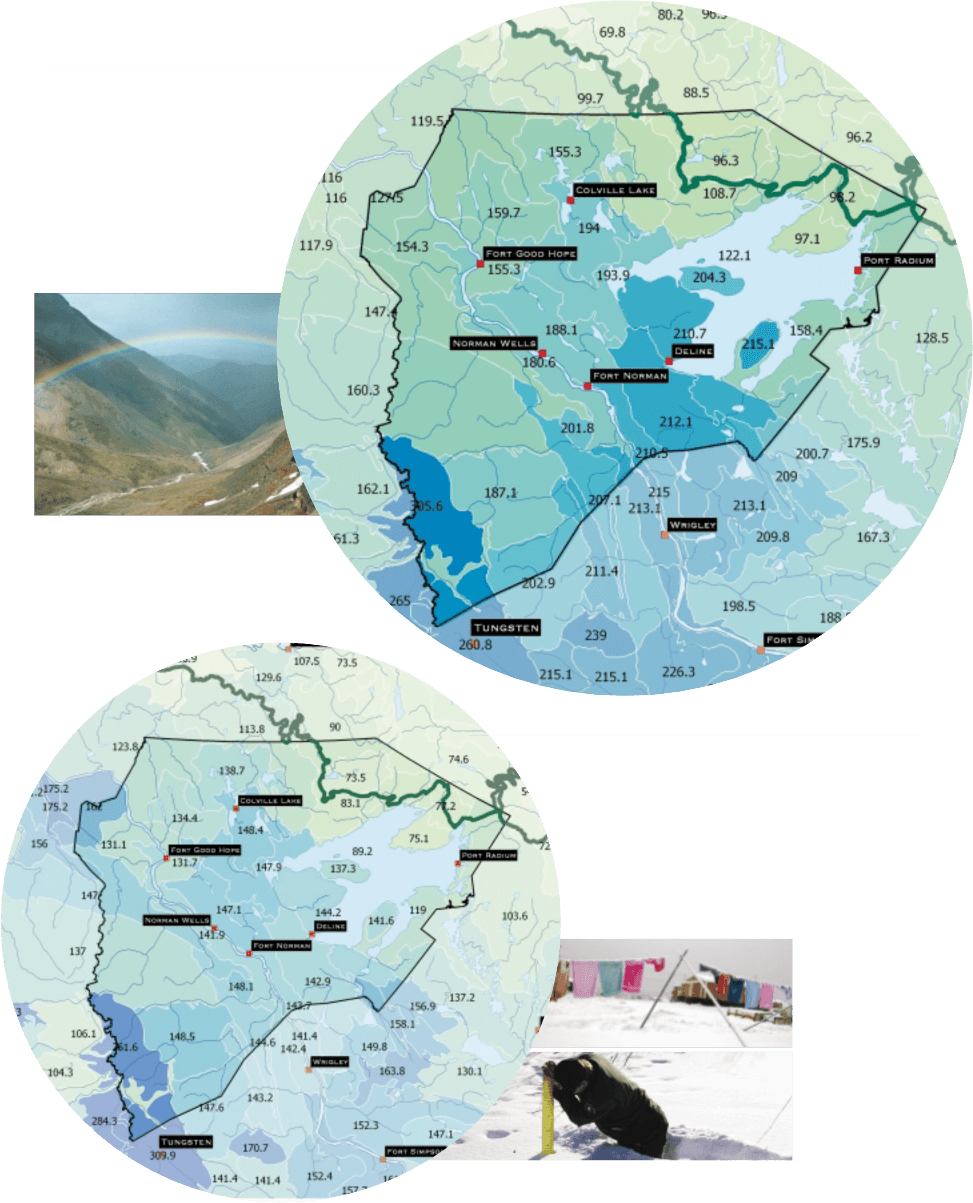

When it rains does it pour?

Total rainfall in millimetres

Estimated average annual precipitation that falls as rain

Snow and rainfall are low by North American standards. Average precipitation throughout the Sahtu is 300-400 mm annually. Precipitation decreases at the more northern latitudes, tapering off to 250 mm at the northern boundary. Daily rainfall in the warmer months rarely exceeds 5 mm. Heavy daily rains from localized storms in the summer however can exceed 50 mm.

Total snowfall in millimetres

Estimated average average annual snowfall throughout the Sahtu

By November precipitation primarily falls as snow. Mean monthly snowfall rises sharply in the autumn and then diminishes through the winter months as the artic high stablilizes and prevents humid air from the Pacific from moving in. Even as snowfall decreases snow accumulation steadily increases throughout the winter due to lack of any significant thaws. Maximum snowpack depth is reached in March then a more rapid decrease in the snowpack occurs as summer approaches.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]