Fort Good Hope

Rádeyı̨lı̨kóé

There’s A Little Town Called Fort Good Hope.

By Miranda McNeely, FGH

There’s a little town called Fort Good Hope, and it is a cultural and traditional town where the Dene and Metis still live off the land.

Some families still stay out on the land. They hunt and fish. The men will set traps and hunt. The women will go about their daily chores such as making dry meat or cutting up the meat. They also cook for their families, and do sewing and cleaning. So all day, every person in the camp is busy. In the evening, they all relax and take it easy.

They would stay out there for three months or two months. When Christmas comes, they travel back by skiddoo to a little town called Fort Good Hope. It takes about seven or eight hours, but it depends where they stayed in the bush.

When they get home, the people hug their family and their kids. They’re glad to be back in a little town called Fort Good Hope.

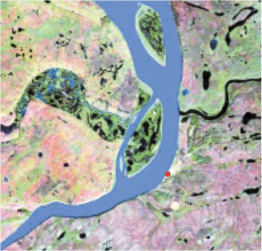

Mackenzie Valley Viewer, 2001

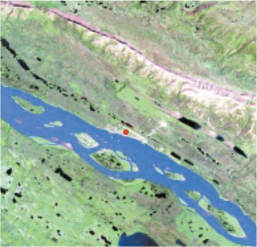

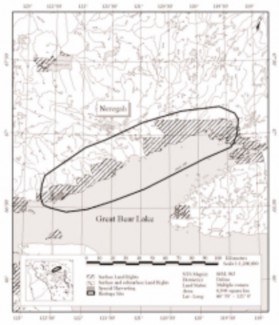

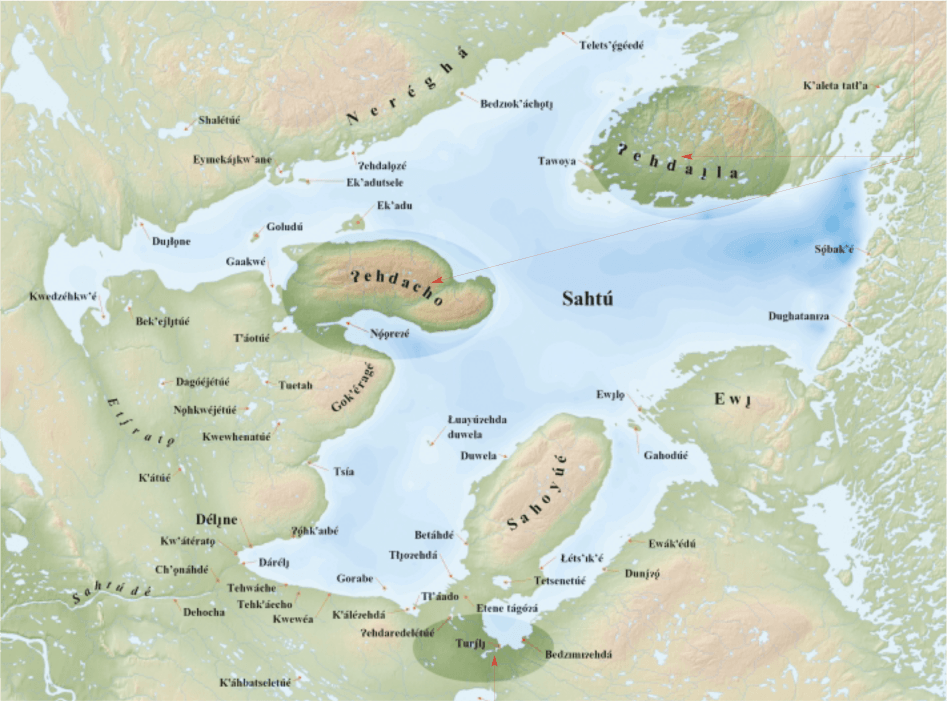

Fort Good Hope is named Rádeyı̨lı̨kóé, meaning “home at the rapids,” for its location below the Ramparts Rapids. The Ramparts also refers to the steep walled river canyon at the rapids. Known as Fee Yee in the local dialect, this is an ancient fishery and spiritual site.

Known in anthropological literature as Hareskin people, the Dene of Fort Good Hope call themselves K’asho Got’ine, or “big arrowhead people.” This may have been confused by early missionaries and anthropologists with the Dene term for rabbit, “gah”; indeed, the people of this area were known for their skill at making woven rabbitskin clothing.

Fort Good Hope was established by the North West Company in 1805 as the first fur trading post in the lower Mackenzie Valley. Thus it became a gathering place for Shita Got’ine, Gwich’in, and even Inuvialuit people of the Mackenzie Delta who came there to trade. Fort Good Hope became the centre of a vast trading network, extending north to Herschel Island and west to Russian Alaska.

A Roman Catholic mission was established by Oblate priest Henri Grollier in 1859, and during the 1960s, Father Emile Petitot worked with local people to construct the first Roman Catholic church in the Northwest Territories. Using paints made with local fish oils, Petitot decorated the church with richly coloured murals.

Fort Good Hope came to national attention in 1975 when the community hosted a hearing of the Berger Inquiry and a documentary film was made about the event. Community members have since played a strong role in documenting traditional environmental knowledge as a basis for defining the terms of economic development, so as to minimize environmental impacts and maximize benefits for Dene and Métis people. Home of the biennial Wood Block Music Festival, Fort Good Hope has nurtured a strong culture of music, including traditional drumming, the Métis fiddle style evolved during the fur trade, and contemporary rock and roll.

photos © Robert Kershaw

Main Street Summer feast

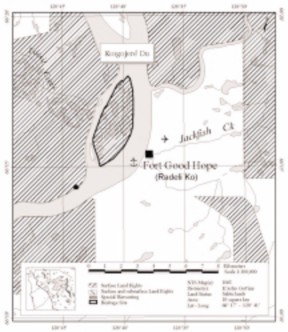

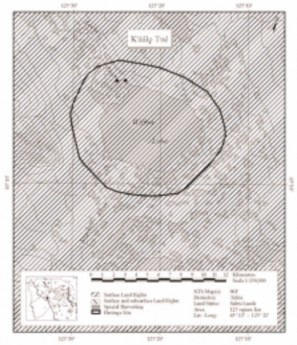

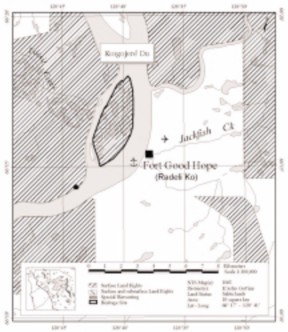

Koigojeré Du / Manitou Island

Manitou Island is used by the residents of Fort Good Hope as a source of firewood, and for small game hunting. The logs for the community complex were cut and hauled from here. Together with its history as a former location of the HBC fort, the island is very important to the community.

Fort Good Hope was established in 1804 by the North West Company, and originally located on the left bank of the Mackenzie River somewhere near Thunder River (Voorhis 1930:75). In 1826, after the 1821 amalgamation with the Hudson's Bay Company, the fort was moved to Manitou Island were it operated until 1836. Flooded, and damaged by ice in 1836, it was moved to its current location on the right bank of the Mackenzie River, across from Manitou Island.

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

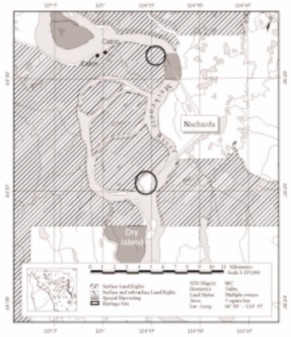

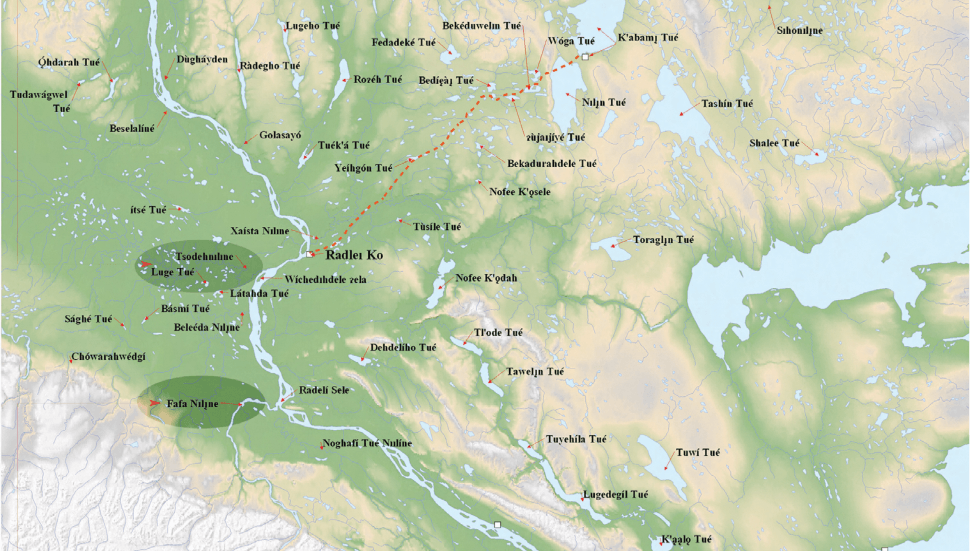

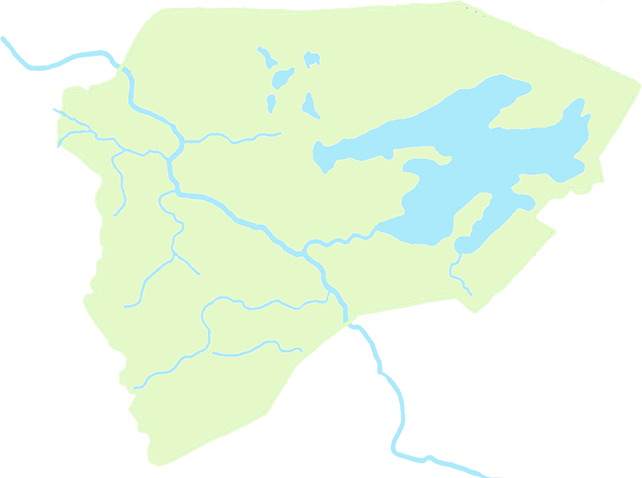

Tsodehnı̨lıne and Tuyát’ah / Ramparts River and Wetlands

The Ramparts River and Wetlands flows from the foothills of the Mackenzie Mountains east to the Mackenzie River, entering it just above the Ramparts Canyon, and the community of Fort Good Hope. The river, meandering through critical wetlands, has been an important hunting, trapping and fishing area for Fort Good Hope families for generations. Particularly important for hunting moose, beaver and muskrats, the area is also known locally as a critical waterfowl breeding site. It is also known as an excellent place to begin teaching young hunters the rules and behaviours necessary for a successful hunt.

The Ramparts River and Wetlands contains many named places including a sacred site, the Thunderbird Place.

Ɂıdıtué Dáyı̨́dá / The Thunderbird Place

Located on a sharp bend in the Ramparts River, the Thunderbird Place is a dangerous place. In times long ago, a giant Thunderbird lived here, and travellers were often killed by it. An elder with powerful medicine killed the Thunderbird, making river travel safe again. There are several places in the Sahtu settlement area where other water monsters live, or have lived, and these places are always considered dangerous, requiring special rituals or practices when travelling nearby. As told by an elder from Fort Good Hope, the story recounts how people still to this day feel uneasy when traveling past the Thunderbird Place:

This was in the ancient days, people who traveled this river would come to this spot and they were killed by the Thunderbird monster, which lived there. Finally, an elder decided to do something to rid this area of this monster. Maybe this man had medicine to understand what made the monster tick. He threw a rock into the water, and from then on there was no problem with it again. Some places the water is muddy and I don’t feel as relaxed as when I go to other places. I always feel uneasy if I'm in this area.

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

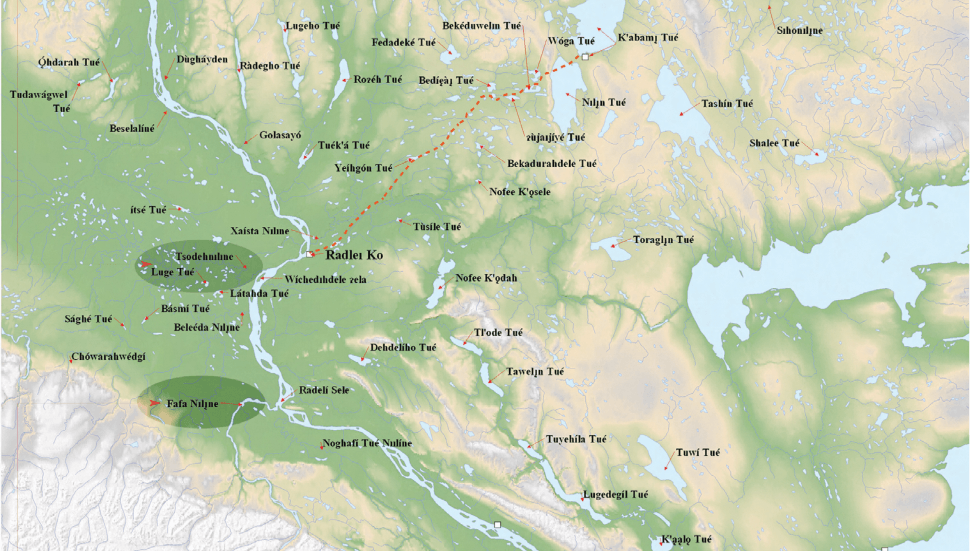

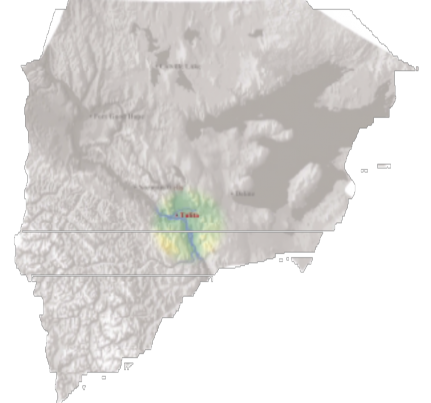

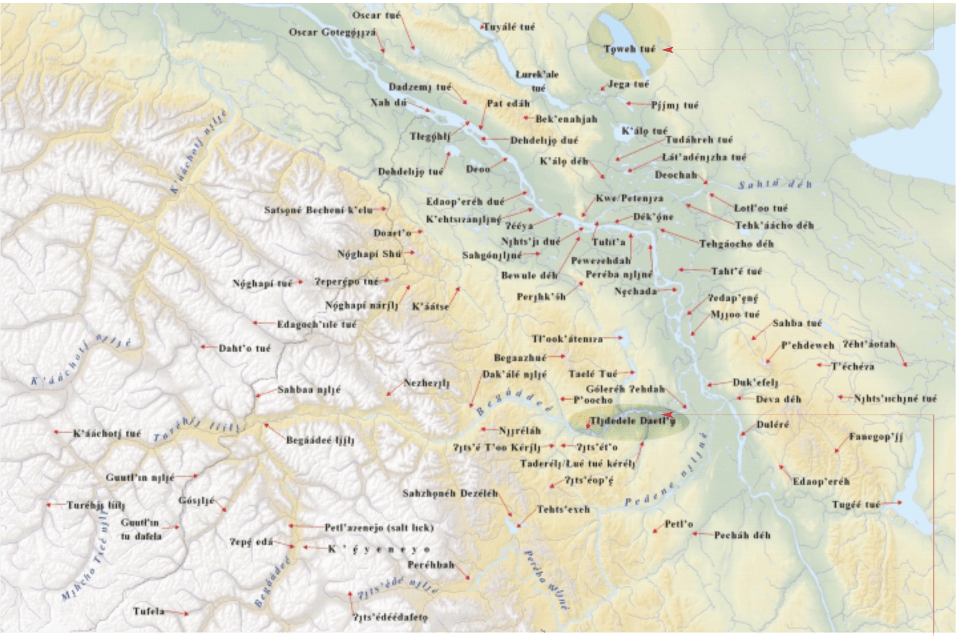

Fort Good Hope/Colville Lake Traditional Place Names project map

Faɂfa Nılı̨́ne / Mountain River

Sheep hunting up Mountain River © R. Kershaw, 2004

An important traditional trail used by Mountain Dene from Fort Good Hope. There are many named places, camping, hunting and fishing locations and many stories associated with the river. In the old days, mooseskin boats were built to float down the river in spring. Many stories recount the trials and tribulations of mooseskin boat travellers attempting to navigate the many dangerous canyons on the river. At the head of the canyons, the boats would stop to let the women and children out to walk over on the portage trail. Only the men would lead the boats through. Today it continues to be an important moose hunting area, and is known as the shortest route to the highest mountains, and sheep hunting areas. Popular with white water canoeists, the river has tremendous tourism potential.

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: