The Sahtu in the 20th Century

The discovery of oil at Norman Wells in 1919 unleashed a new dynamic in the region. The signing of Treaty 11 a year later provided the legal basis for developing the oil wells. A rapid influx of southerners increased the exposure of Dene people to deadly epidemics. In 1928, a devastating flu epidemic took the lives of about 600 people in the Mackenzie District of the Northwest Territories, about 10-15% of each village. Tuberculosis and pneumonia spread in the wake of the epidemic, preying upon the weakened survivors. Between 1937 and 1941, tuberculosis was found in the District at a rate fourteen times the national average, and pneumonia at a rate of more than double the average. One Edmonton doctor visiting the NWT noted in 1934 that he could not find “a single physically sound individual” (quoted in Abel 1993, 208).

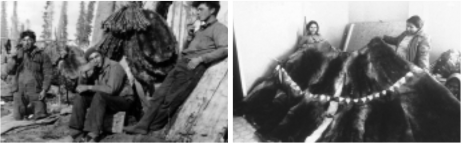

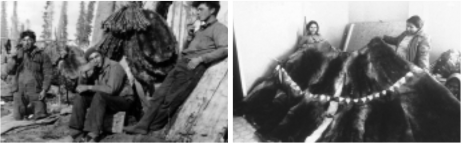

Top - Hunters travelling by dog sled

Middle - Madeline Karkagie (Tulita) smoking hide.

Bottom - Caribou meat ready for transport

photos © Norm Simmons

Bishop Gabriel Breynat was a tireless advocate for the sick and destitute Dene peoples. In 1938, he wrote an article entitled “Canada’s Blackest Blot” that was published in the Toronto Star Weekly, in which he noted that in “carefully compiled figures for 12 months during 1935-1936 (an exceptionally good year), it is estimated that the per capita income of these Indians was $110” (quoted in Fumoleau 1996, 300).

Increasingly restrictive fur and game harvesting laws were an additional blow to Dene peoples, who already felt betrayed by broken promises in the aftermath of Treaty 11. In 1928, closed seasons on beavers were imposed, and further restrictions were added in amendments to the Game Act in 1929. This was despite evidence that non-aboriginal trappers from the south were having the greatest impact on wildlife populations.

Fortunately, the game laws probably did not have much impact on the communities of the Sahtu. Many people were not aware of the laws, and local agents and police likely recognised the futility of attempting to enforce them (Abel 1993). However, by the end of the 1930’s, the Depression was affecting the Mackenzie Valley as fur prices crashed. An era that lasted 140 years in the Sahtu was coming to a close.

Meanwhile, the discovery of pitchblende at Port Radium on Great Bear Lake and gold at Yellowknife marked a turning point in the economy of the Mackenzie District in the 1930s. The opening of the Sǫmba K’e (Port Radium) mine on Great Bear Lake in 1933 created a new home market for oil. Production of petroleum at Norman Wells increased at a dizzying speed, especially with the additional demand created in 1937 by the opening of gold mines in Yellowknife. Imperial Oil built a new refinery, and drilled two new wells. Production went from 910 barrels per year in 1932 to over 22,000 in 1938. In 1946, mineral production exceeded fur production in value, for the first time in the north.

Today, the economy of the Sahtu Region is based on a mix of industrial resource extraction, tourism, traditional trapping and subsistence harvesting. People of the Sahtu continue to rely on the land as a source of income, food, security and identity. Many Dene and Metis people have found ways to combine wage employment in town with traditional activities in the bush. Although young people are learning modern skills in school, there is also a movement to ensure that they are provided with teaching by their elders in the skills and knowledge needed for survival on the land.

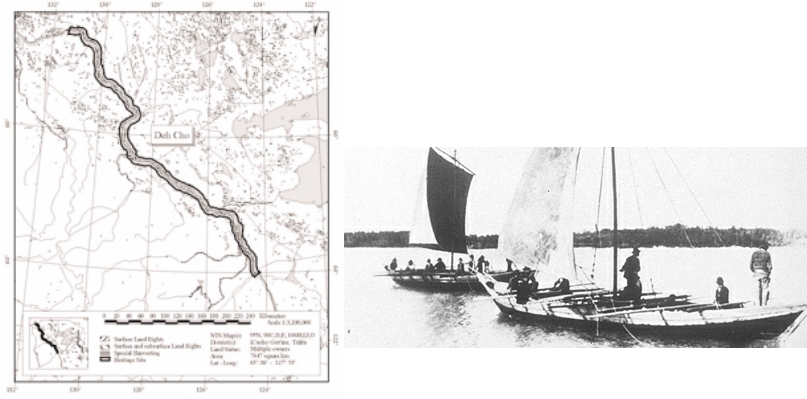

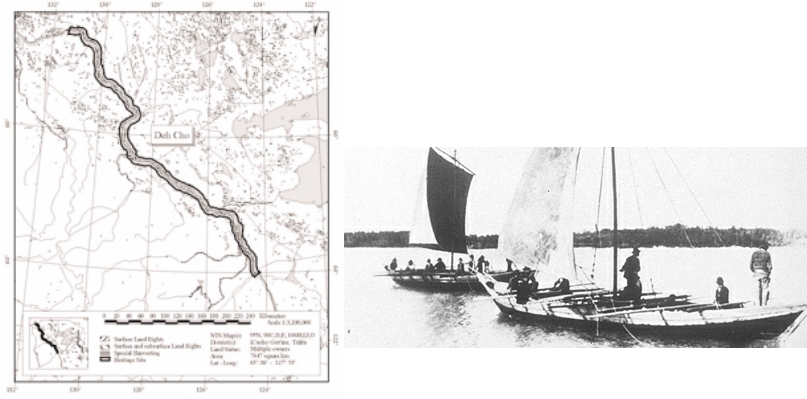

Deh Cho (Mackenzie River)

The Deh Cho or 'Big River', from Blackwater River in the south, to Thunder River in the north, was and remains a very important route for Sahtu Dene and Metis... As a traditional use area, the Deh Cho continues to provide domestic fisheries, moose and waterfowl hunting areas, travel access to many other locations. It is associated with numerous legends, including stories of Yamoria.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Fur Trade

The people of the Sahtu were introduced to a fur trade economy by way of traditional trade routes with the Dene Suåline (Chipewyan) people, long before European traders made their way to the area. The northern fur trade era with the English and French traders began in 1670. Under a Royal Charter, the Hudson Bay Company was given ownership of the lands drained by the Hudson Bay. Over the next 100 years, trading centred in this region known as Rupert’s Land. It was not until trade routes were established further north and west that traders looked to the Sahtu.

At the turn of the 18th century, fur trading posts under the North West Company were established in the Sahtu after Alexander Mackenzie’s exploration of the Deh Cho River. The North West Company established a post in Deline (Fort Franklin) in 1799, in Tulita (Fort Norman) and in the vicinity of Fort Good Hope in 1804-1805. In 1821, the North West Company joined the Hudson’s Bay Company. A century of relationships developed through the fur trade gave rise to the Métis Nation, a distinct people that brought together Dene and European cultures.

In the early days of the fur trade, the Dene would seldom trap a locality out. Subsisting out on the land, they would move camp often in search of game and would consequently trap lightly over a large area.

But fur was a lucrative commodity for European traders, and the trade rapidly expanded, exerting new pressures on fur-bearing animal populations. Early on, ships that delivered £650 worth of trade goods were returning to England with £19,000 worth of furs. Europeans increasingly found it profitable to enter the trade as trappers. In contrast to their nomadic Dene counterparts, European trappers brought most of their own provisions, established themselves in a chosen locality, built headquarters with small buildings and devoted most of their time to trapping to supply the market. In a few years, nearby fur-bearing populations would be exhausted, forcing them to seek new trapping areas.

As the 20th century dawned, trapping had become an established modern, market-driven activity. However, over-trapping and over-hunting were causing severe shortages of the wildlife that had been the source of survival for the Dene and Métis peoples. The tensions of those times are evoked in Dene bushman stories, which are said to be a response to the fearsome white strangers that had entered the wilderness.

WHEN THE BUSHMAN CAME TO TOWN

By Corey Chinna, Gr 7-12, Fort Good Hope

(Originally printed in the Mackenzie Valley Viewer, February 2001)

I was just coming from my friend’s house when I saw some kids riding around on skidoos. So I ran home to get my skidoo. I grabbed the skidoo from my house, and took off to follow the other kids. By the time I caught up with them, it was already dark. I just followed the skidoo in front of me.

Then I heard a weird noise coming from the engine. So I stopped to check it out. It didn’t look like anything was wrong. I kicked the engine, and it went back to normal. I jumped back on and took off again.

All the kids were gone already, except one. So I followed him. He slowed down and stopped. I asked him if he knew where the other kids went. He didn’t answer. I looked at his clothes. They were all hair! I remember my granny telling me a bushman was wandering around.

Then he stood up. He was about seven feet high, and hairy, too. He started grumbling like he was talking. I took off around a corner. I thought I’d lost him, so I said, “Whooo!” Then he jumped out of the bushes and covered my eyes so I couldn’t see. I crashed into a ditch. When I turned around, he wasn’t there. I went to the road to see if I could see him. I said, “Aah, I guess I’ll go home and tell my dad about the skidoo.”

Then I turned and there he was, towering over me like a giant. He grabbed me and picked me up. Suddenly something came out of nowhere and crushed the bushman. He was out cold. Later, I saw his arm move, so I ran.

He was running after me. I ran onto the river, which it wasn’t very frozen. I kept running, and all of a sudden he fell through the ice. I checked to see if he fell in for sure. Then his big hand came out and grabbed my leg. I pulled out my lighter and burned his hand. Then he went back under. I ran home to warm up.

Mackenzie’s Mistake

On June 3,1789 25 year old fur trader Alexander Mackenzie, led his 12-person crew of French-Canadian voyageurs and Chipewyan guides and their fleet of birchbark canoes into the cold water of Lake Athabasca. He had every reason to believe that the voyage would lead westward to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

The Pacific quest however was difficult from the outset. Progress on the Slave River, leading north was slow, and dangerous. Unseasonable ice on Great Slave Lake often brought the fragile birchbark canoes to a standstill.

The sagging spirits of the crew lifted when the next great river (Deh Cho) began to carry them westward. Soon the snow-capped wall of the Rocky Mountains in the distance appeared. But when the river itself turned north and parallel to the mountains, at Camsell Bend, the paddlers realized that their quest for the Pacific would be a failure.

On July 16, 6 weeks after their optimistic departure their fears were confirmed: their route had taken them not to the Pacific Ocean, but to the Arctic. Disappointed, Mackenzie and his guides paddled back to Lake Athabasca.

In May of 1793, Mackenzie tried a second time. This time he headed west from Athabasca, following the Peace River to the continental divide and reached the headwaters of the Fraser River which flows into the Pacific at present-day Vancouver.

His guides knowing the river's dangerous reputation advised Mackenzie against attempting to descend it. Instead, the explorer descended the Bella Coola River, becoming the first European to cross North America north of Mexico.

Adapted from Canadian Council for Geographic Education’s “Mackenzie River - Wrong Turn.”

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

An Ancient Heritage

Over thousands of years, the Dene peoples of the Sahtu Region have adapted to an unforgiving environment that demands highly specialised skills and knowledge. Traditional knowledge has been transmitted orally from generation to generation. Some of the oral history and traditional practices have been documented by early missionaries and fur traders, and more recently by anthropologists and community researchers. Archaeologists have also documented traces of ancient human habitation in sites throughout the region. Dene communities continue to keep many of the traditional landbased practices and stories alive, adapting them to the modern context.

The pattern of traditional Dene life follows the changing seasons and movement of wildlife, with major changes marked by autumn freeze-up and spring thaw. Barrenland caribou are an important subsistence resource, and communal hunts during the fall migration are occasion for large community gatherings on the land where meat and hides are processed. This is also a good time for picking berries and harvesting herbal medicines. During the winter, families disperse to their traplines, often located in their traditional clan area. Moose and woodland caribou hunting also requires dispersal in smaller groups. The spring geese and duck migration provides another opportunity for larger gatherings. During the summer, camps are set up for communal processing of fish harvests. Dene people are experts at food preservation; dried and smoked meat and fish are prized delicacies in bush and town alike.

The four Dene peoples of the Sahtu have distinct dialects and practices. These are dynamic, informed by a long history of interaction among aboriginal peoples within the region and beyond. Linguists identify the North Slavey language of the Sahtu as part of the Athapaskan language group, which includes peoples stretching across the northwest from Alaska to Nunavut, and south to California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and into northwestern Mexico. Linguists and archaeologists theorize that Athapaskan peoples may have migrated from Siberia across the Bering Strait, and dispersed from Alaska eastward and southward, gradually evolving distinct languages and dialects. Old time stories told by various Athapaskan peoples also tell of dispersals caused by catastrophic events.

Today the ancient relationships among the northern Dene peoples are kept alive in regional gatherings attracting people from throughout the Northwest Territories and as far away as the western Yukon and eastern Nunavut. Cooperative hunts, spiritual gatherings and family celebrations are all occasions for drum dances, hand games and storytelling. In the Sahtu Region, this tradition now encompasses a wide variety of regional events including sporting events and cultural festivals. And now more than ever in the post-land claim era, there are gatherings to make strategic decisions on matters of common interest. Young men and women are encouraged to seek marriage partners from other communities, so family relationships continue to extend across the region and beyond.

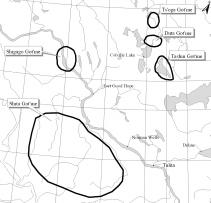

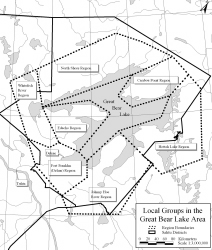

Traditional Clan Areas

There is a traditional Dene land tenure system in the Sahtu Region. This system evolved in recognition of the areas that extended families or clans had established for their own use.

The dispersal of Dene people in small groups was crucial for survival in the days before grocery stores, motorboats and skidoos. People had to be close to enough wildlife for subsistence. In harsh climates, wildlife tends to be dispersed at lower population densities. So it makes sense that people would spread out as well.

The clan area is an important aspect of people’s sense of identity. In the old days, people would know the land of that area intimately. This would be the area where they would establish seasonal campsites. It would be where their children were born and where their ancestors were buried. Many of the family stories passed down through the generations would be set in the clan area, mapping its history.

The clan system of land tenure was not incorporated into the Sahtu Dene and Métis Land Claim Agreement. However, the clan system is still alive in a modified form. Some research has been done to map clan areas, but this has not been systematic or comprehensive.

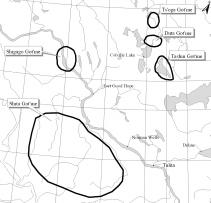

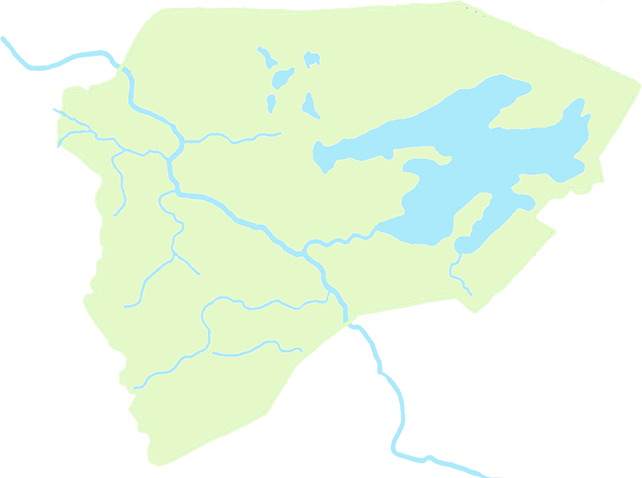

Clan areas around fort good hope and colville lake

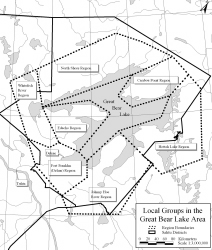

Clan areas around great bear lake

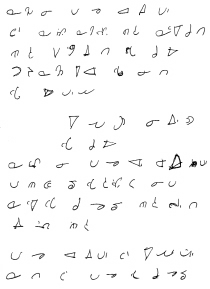

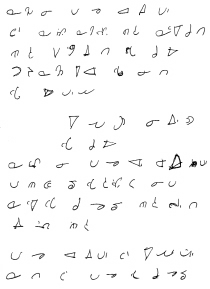

In the Words of Our Elders

[Dene k’ı̨ syllabics by elder Leon Modeste, of Deline Narration in Dene language transcribed and translated by Alfred Masuzumi Originally published in the Mackenzie Valley Viewer, June 2001]

We are Dene wá (the people). So, with our words, with our personal endeavours, we have to protect our interests. We can’t ignore opportunities. It would not be right. We have to love each other. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. We Dene wá have survived by righteous rules, and we are courageous in helping each other, by doing good, and being happy. So by helping one another, everyone feels content.

We Dene wá have to keep what we have through our personal endeavours, and through our words. We can’t ignore our opportunities. It would not be right. We have to love one another.

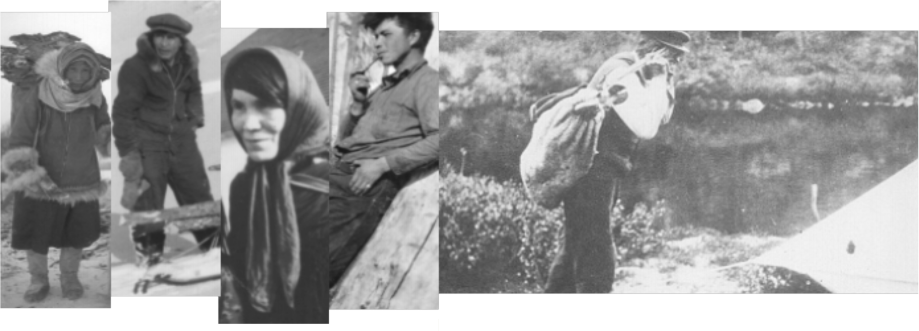

Spring hunt with Joe Modeste Leon Modeste’s father (1977)

courtesy of Leon and Cecil Modeste

Leon and Cecil Modeste

We Dene wá have to survive by righteous rules, and we are courageous in helping one another. We should be content with our lives. For we are Dene wá, and we have survived by helping one another. So in general, the dene feel content.

Traditional Cultural Groups

Traditionally, the Sahtu Dene organized themselves into regional bands, each associated with a distinct dialect of Slavey language and each with a particular 'home' land use area. Membership was fluid however, and people accessed the entire area. Though all of the regional bands shared a common culture, many had their own stories, culture heroes, and places, creating unique cultural and social identities. The four major cultural groups within the region are: the K’ahsho Got’ine (Hare people), the Shita Got’ine (Mountain people), the K’áálǫ Got’ine (Willow Lake), the Sahtú Got’ine (Great Bear Lake people). The land claim agreement defined three districts that roughly correspond to these cultural groupings.

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: