The Sahtu Land Claim

Forging a new map: The Sahtu Land Claim

The Sahtu Land Claim Agreement was negotiated with the government of Canada to clarify land title, and to enshrine the ongoing role of Dene and Metis people as stewards of the land.

As Long As This Land Shall Last: Treaty 11

The idea of establishing land title and boundaries dates back to 1920, soon after the first oil gusher was hit at Norman Wells. The nascent Council of the Northwest Territories began planning for the development of oil and gas reserves. But the aboriginal peoples had not ceded their rights to the territory. When it was pointed out that oil and gas licenses in this area existed outside the law, the Department of Indian Affairs undertook to conclude Treaty 11. The Crown considered this to have been accomplished in the summer of 1921, during a brief trip through the communities along the Mackenzie River. According to the treaty document, Dene and Metis peoples ceded their title to 599,000 square kilometres, stretching northward from the 60th parallel to the Arctic Ocean, and eastward from the Mackenzie Mountains to Great Slave Lake. Oral testimony shows that the Dene people did not understand the Treaty to be extinguishing title to their traditional lands.

Land Title And The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline

Disparities between Dene and government interpretations of Treaty 11 came to light in the late 1960s, when a natural gas pipeline through the Mackenzie Valley was first proposed. In 1966, the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories launched an oral history project to determine the Dene understanding of the Treaty 11 process. On March 24, 1973, sixteen Dene chiefs put forward a legal claim of interest in an area covering more than one million square kilometres, and presented a caveat for registration under the Land Titles Act. Nearly six months later, Justice William G. Morrow presented a finding that the Dene peoples did indeed have aboriginal rights in the area. This caveat meant that no development could proceed until land title was established.

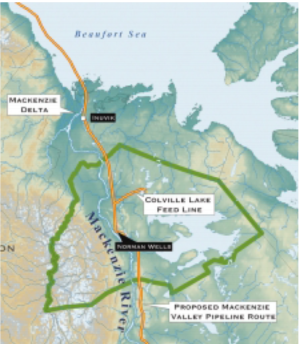

In 1974, the federal government set up a commission to investigate the “terms and conditions that should be imposed” in respect of the proposed pipeline. Justice Thomas Berger led the inquiry. Over a three year period, Berger travelled throughout the Western Arctic in an unprecedented consultation process involving more than a thousand witnesses. When the Berger Inquiry came to the Sahtu Region, people had their first opportunity to voice their opinions about the impact that such a major development would have on their land and their lives. In his final report, Berger recommended a moratorium on development until aboriginal land claims could be settled.

Taking Treaty In Tulita: Remembering Treaty 11

The people were scared to take the treaty because they didn’t know what was coming. The Treaty party couldn’t just come to the town and say, “Here, we’ll give you the money for nothing.” The Indians had feelings that the White people were going to take over something, that the White people were not giving the money away for nothing. They must be buying something, either the land or the people. That’s how the Indians felt. So they just kept asking the White people what the money was for. They said, “You just can’t give us the money for nothing. It must mean something …” The White people kept bugging the people for treaty. They said, “You’ve got to take treaty.” The people said no. So everyone went home. The next day, it was the same thing again. They talked about taking the Treaty all day. They tried to force the people to take the Treaty. The people didn’t want it

From interviews with Joe Kenny, Albert Menacho (Isadore Yukon, interviewer), John Blondin and Johnny Yakeleya (Bernard Masuzumi, Interviewer), and notes by John Blondin, in As Long As This Land Shall Last, by Rene Fumoleau, OMI (Toronto: University of Calgary Press, 1975, 2004). 231-232.

Dene Nation Assembly, Tulita, 2001

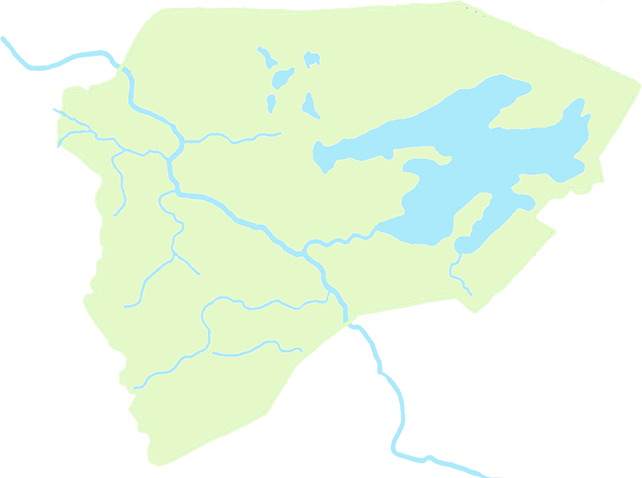

The Sahtu and surrounding land claim regions and territories

Recognizing unfulfilled treaties throughout the NWT, the federal government established mechanisms for land claim negotiations. The first settlement was concluded with the Inuvialuit in 1984. The Dene and Metis came together and put forward a single Denendeh land claim. By 1988, Agreement-In-Principle was reached on this claim. However, the agreement fell apart over a number of issues. The Gwich’in communities withdrew from the process, soon followed by the Sahtu communities. In 1991, the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement was signed. The Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement was concluded in 1993.

The New Land Claim Map

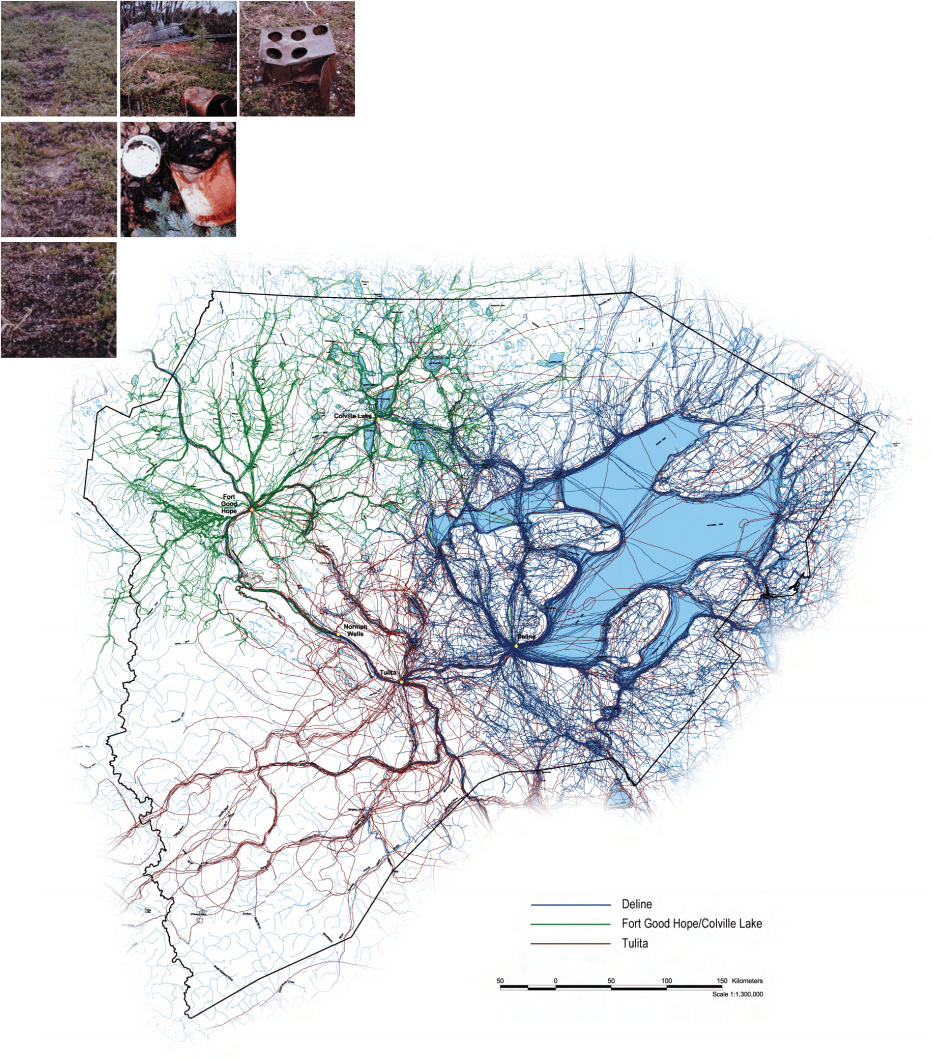

The Sahtu Land Claim map involves multiple layers of boundaries: the boundary defining the region as a whole, referred to in the Land Claim as settlement lands; boundaries identifying three districts within the region; five municipal boundaries; and outside the municipalities, numerous boundaries defining federal, territorial and aboriginal land title.

The regional and district boundaries are necessarily provisional to some extent, given that there is overlap in traditional land use areas; fixed boundaries did not exist in the old clan area system. Although this issue affects all aboriginal lands in three northern territories, it is especially complex for the Sahtu since it is centrally located, sharing boundaries with the Yukon First Nations to the west; the Gwich’in, Inuvialuit and Nunavummiut(the people of Nunavut); the Dogrib of the North Slave region covered by Treaty 11 to the east, and the Deh Cho First Nation tothe south .

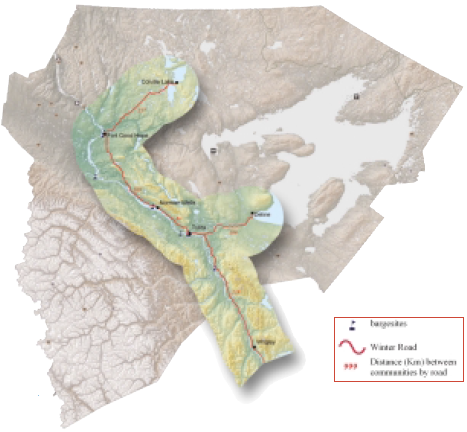

Districts And Communities

The district boundaries were defined roughly corresponding with the core land use areas of the contemporary Dene and Metis communities within the Sahtu Region. Though the nomadic Dene had harvested in these areas for generations, permanent settlements were established relatively recently, in response to the expansion of the fur trade and subsequently, the development of petroleum and mining industries in the area. As the non-aboriginal population increased and wildlife became more scarce, it became increasingly difficult to sustain a wholly land-based subsistence. When the Federal government finally recognized its responsibility for the well-being of northern aboriginal peoples, they were encouraged to settle in centres established for convenient administration of services. Land use patterns shifted somewhat to accommodate a new hybrid way of life, combining town and bush.

Fort Good Hope and Tulita were both established early in the 19th century as fur trading and mission posts conveniently located along the Mackenzie River transportation route. Norman Wells, as its name implies, is a primarily non-aboriginal and Métis community founded as a result of the “discovery” of oil there in 1919 (though the aboriginal inhabitants of the area may well have known about this long before). Deline developed as a semi-permanent community on Great Bear Lake near the mouth of Great Bear River in the 1940s and 1950s with the expansion of the Port Radium uranium mine. The community achieved permanence with the closure of the mine in 1960, when the Dene residents of Port Radium were compelled to move to Deline. Colville Lake was created in 1962 as part of a movement to revive traditional trapping practices, linked to the establishment of a Roman Catholic mission there.

Although there are close interrelationships among the Dene communities, they are culturally and linguistically distinct. The K’ahsho Got’ine/Hare people are now centred in Fort Good Hope and Colville Lake. The Shita Got’ine/Mountain people have joined with the K’áálǫ Got’ine/Willow Lake people in the community of Tulit’a. The Sahtúot’ine are named after Sahtú/Great Bear Lake, and are based in Deline. Métis people, descendents of relationships established between Dene people and fur traders, reside in all five communities of the region.

The Berger Inquiry In Fort Good Hope

The following is excerpted from the address given by Chief Frank T’Seleie at the Pipeline Inquiry during its visit to Fort Good Hope, August 5, 1975.

Mr. Berger, as chief of the Fort Good Hope Band I want to welcome you and your party to Fort Good Hope. This is the first time in the history of my people that an important person from your nation has come to listen and learn from us, and not just come to tell us what we should do, or trick us into saying “yes” to something that in the end is not good for us …

It is not at all inevitable that there will be a pipeline built through the heart of our land. Whether or not your businessmen or your government believes that a pipeline must go through our great valley, let me tell you, Mr. Berger, and let me tell your nation, that this is Dene land and we the Dene people intend to decide what happens on our land….

Mr. Berger, you have visited many of the Dene communities. The Dene people of Hay River told you that they do not want the pipeline because, with the present development of Hay River, they have already been shoved aside. The Dene people of Fort Franklin [Deline] told you that they do not want the pipeline because they love their land and their life and do not want it destroyed. Chief Paul Andrew and his people in Fort Norman [Tulita] told you that no man, Dene or white, would jeopardize his own future and the future of his children. Yet you re doing just that if you asked him to agree to a pipeline through this land ….

Our Dene nation is like this great river. It has been flowing before any of us can remember. We take our strength and our wisdom and our ways from the flow and direction that has been established for us by ancestors we never knew, ancestors of a thousand years ago. Their wisdom flows through us to our children and our grandchildren to generations we will never know. We will live out our lives as we must and we will die in peace because we will know that our people and this river will flow on after us.

From Watkins, Ed. Dene Nation: The Colony Within. (1977: 12-17).

Northern Frontier Northern Homeland: The Berger Report

Justice Thomas Berger summarized the key points from his extensive report in a letter to Warren Allmand, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, dated April 15, 1977. Below are excerpts from Berger’s letter.

We are now at our last frontier. It is a frontier that all of us have read about, but few of us have seen. Profound issues, touching our deepest concerns as a nation, await us there.

The North is a frontier, but it is a homeland too, the homeland of the Dene, Inuit and Metis, as it is also the home of the white people who live there. And it is a heritage, a unique environment that we are called upon to preserve for all Canadians.

The decisions we have to make are not, therefore, simply about northern pipelines. They are decisions about the protection of the northern environment and the future of northern peoples…..

The Mackenzie Valley

I have concluded that it is feasible, from an environmental point of view, to build a pipeline and to establish an energy corridor along the Mackenzie Valley, running south from the Mackenzie Delta to the Alberta border. Unlike the Northern Yukon, no major wildlife populations would be threatened and no wilderness areas would be violated....

However, to keep the environmental impacts of a pipeline to an acceptable level, its construction and operation should proceed only under careful planning and strict regulation. The corridor should be based on a comprehensive plan that takes into account the many land use conflicts apparent in the region even today....

Economic Impact

The pipeline companies see the pipeline as an unqualified gain to the North; northern businessmen perceive it as the impetus for growth and expansion. But all along, the construction of the pipeline has been justified mainly on the ground that it would provide jobs for thousands of native people....

Although there has always been a native economy in the north, based on the bush and the barrens, we have for a decade or more followed policies by which it could only be weakened and depreciated. We have assumed that the native economy is moribund and that the native people should therefore be induced to enter industrial wage employment. But I have found that income in kind from hunting, fishing and trapping is a far more important element in the northern economy than we had thought.

The fact is that large-scale projects based on non-renewable resources have rarely provided permanent employment for any significant number of native people. There is abundant reason to doubt that a pipeline would provide meaningful and ongoing employment to many native people....

It is an illusion to believe that the pipeline will solve the economic problems of the North. Its whole purpose is to deliver northern gas to homes and industries in the South. Indeed, rather than solving the North's economic problems, it may accentuate them.

The native people, both young and old, see clearly the short term character of pipeline construction. They see the need to build an economic future for themselves on a surer foundation. The real economic problems in the North will be solved only when we accept the view the native people themselves expressed so often to the Inquiry: that is, the strengthening of the native economy. We must look at forms of economic development that really do accord with native values and preferences. If the kinds of things that native people now want are taken seriously, we must cease to regard large-scale industrial development as a panacea for the economic ills of the North...

If There Is No Pipeline Now

An economy based on modernization of hunting, fishing and trapping, on efficient game and fisheries management, on small-scale enterprise, and on the orderly development of gas and oil resources over a period of years - this is no retreat into the past; rather, it is a rational program for northern development based on the ideals and aspirations of northern native peoples.

To develop a diversified economy will take time. It will be tedious, not glamorous, work. No quick and easy fortunes will be made. There will be failures. The economy will not necessarily attract the interest of the multinational corporations. It will be regarded by many as a step backward. But the evidence I have heard has led me to the conclusion that such a program is the only one that makes sense....

Implications

I believe that, if you and your colleagues accept the recommendations I am making, we can build a Mackenzie Valley pipeline at a time of our own choosing, along a route of our own choice. With time, it may, after all, be possible to reconcile the urgent claims of northern native people with the future requirements of all Canadians for gas and oil.

From Northern Frontier Northern Homeland: The Report of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, revised edition (Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 1977, 1988). 14-29.

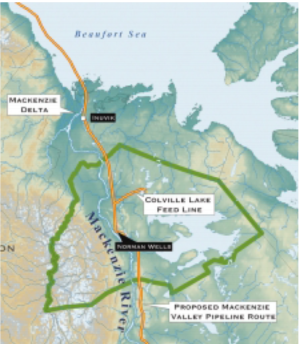

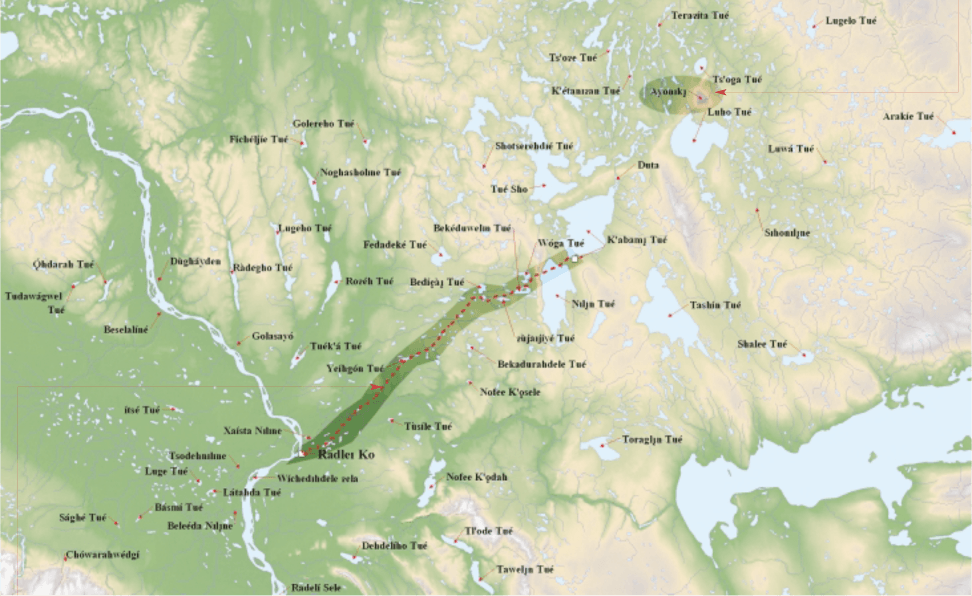

Proposed Mackenzie Valley pipeline through the Sahtu

Land Title , Administration and Governance

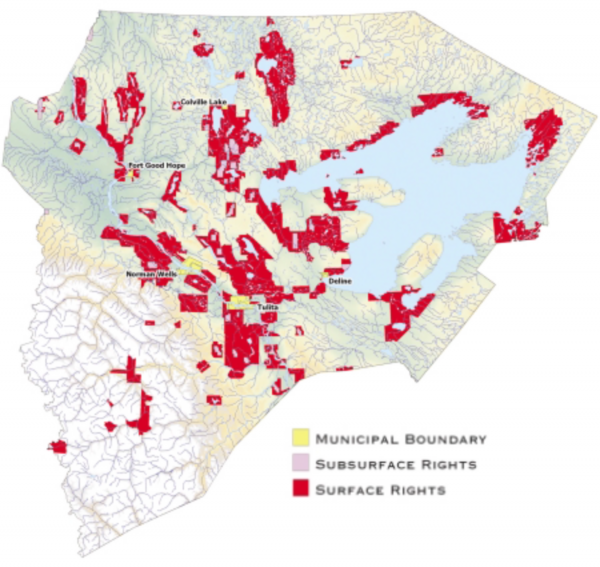

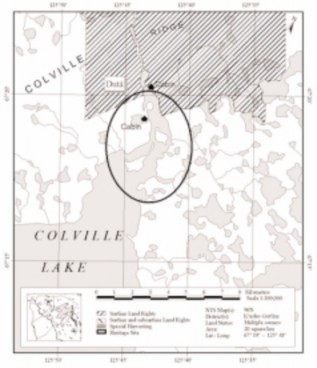

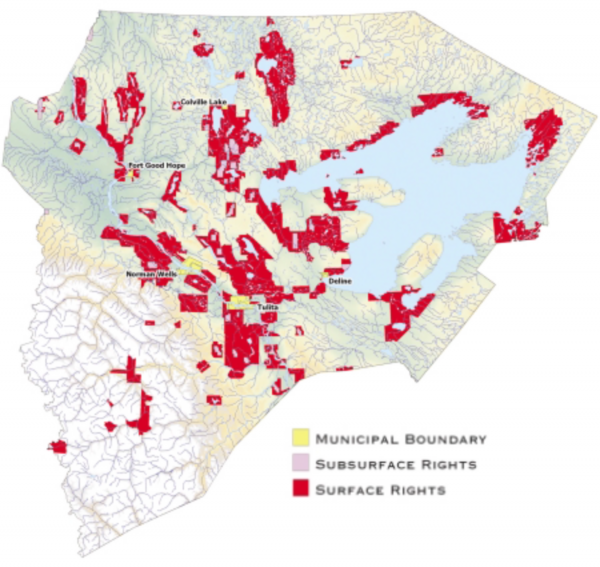

The Sahtu Dene and Metis of the three Districts now have title to 41,437 square kilometres of settlement lands, of which 1,838 square kilometres or 22.5% includes the ownership of subsurface resources (petroleum and minerals). Sahtu Dene and Metis lands were selected according to a variety of criteria, including spiritual sites, traditional land use and harvesting areas, and some lands with resource revenue potential. In addition, a number of Special Harvesting Areas have been set aside for land claim beneficiaries.

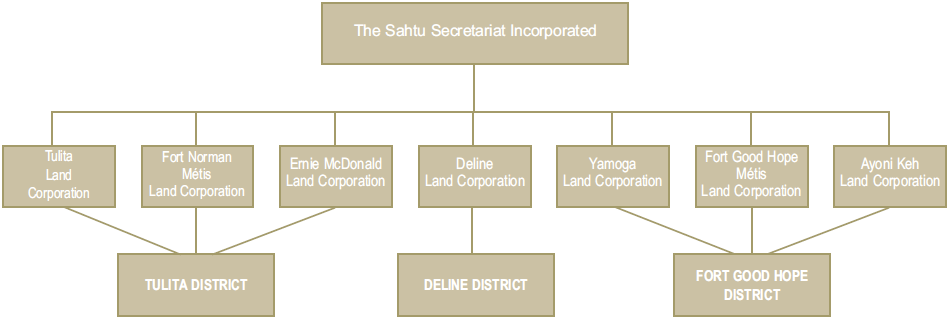

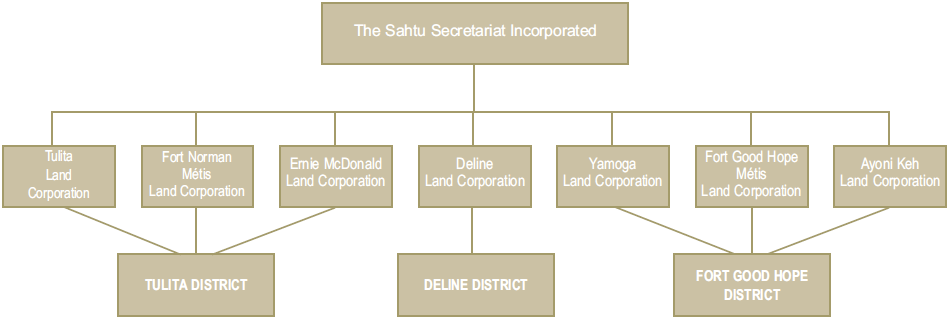

The Land Claim provided for the transfer of settlement lands outside the municipalities in return for a Federal payment of $75 million to designated organisations accountable to Sahtu Dene and Metis beneficiaries. Administration of Land Claim funds and activities on behalf of Land Claim beneficiaries is accomplished by way of seven community Land Corporations (including separate Dene and Metis organisations in Tulita and Fort Good Hope) and the regional Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated. Political leadership for Dene beneficiaries is provided by local Band Councils, and the regional Sahtu Dene Council.

The Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated (SSI) is the coordinating body for the seven Land Corporations and is the main contact for federal and territorial governments with respect to education, health, environment and economic development. The SSI also holds land claim funds in trust for the land corporations, and facilitates corporate decision-making at a regional level.

The local Band Councils and regional Sahtu Dene Council are the political bodies responsible for treaty matters and matters relating to the Indian Act. The Band Councils play an important leadership role in determining community priorities, and administer a number of social programs. The Sahtu Dene Council reviews and makes decisions on issues that influence the way in which Sahtu business is conducted, and provides advice to the SSI.

The Land Claim also provides for the negotiation of self-government agreements with the Federal and Territorial governments. Deline was the first Sahtu community to undertake negotiations and an Agreement-in-Principal was signed August 23, 2003.

The Fight For A Land Claim

At the time of the Berger Inquiry, George Barnaby of Fort Good Hope was an elected member of the Territorial Council representing the Mackenzie/Great Bear region. He resigned while in office, following which he was elected Vice-President of the Indian Brotherhood of the NWT (now known as the Dene Nation). He became a leading proponent of the Denendeh comprehensive land claim agreement.

“The land claim of the Dene is a claim not only for land but also for political rights. Up to this time the native people have had no say in what happens on their land. Everything has been decided by Ottawa or a few people in Yellowknife. This does not apply to development on the land only, but also in the way we live. Laws are made by people from the south that do not make sense to us, but which we have to live by. These laws are to serve the system of the south. They are not laws to protect the Dene way of life.

The land claim is our fight to gain recognition as a different group of people – with our own way of seeing things, our own values, our own life style, our own laws.

The land claim is a fight for self-determination using our own system with which we have survived till now. This system is based on community life. Whether it be a settlement or a trapping camp, whether people live by working in a wage economy or off the land, the laws we follow are concerned with all the people, not to benefit a few at the expense of the rest.”

The land claim is our fight to survive as a nation and to decide our own future.

From Dene Nation: The Colony Within, Mel Watkins, Editor (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977). 120-124.

Surface, Sub-Surface Rights And Municipal Districts

Settlement and Municipal Lands

Under the Sahtu Land Claim Agreement the Sahtu Dene and Metis have title to 41,437 square kilometers of settlement lands of which 1,838 square kilometers includes the rights to subsurface resources. These Sahtu-owned lands are privately owned in fee simple and not reserves under the Indian Act. Municipal lands are fee simple title lands within the municipal boundaries excluding subsurface title.

Federal Crown Lands

Over 80 percent of land within the SSA are Federal Crown lands. On these lands the Government of Canada owns and controls most of the lands and resources, both surface and subsurface.

Commissioners Lands (Block Transfers)

These are lands within or near municipal boundaries of communities where control of surface rights have been transferred to the Commissioners of the NWT. The Commissioner therefore acts like an owner and is able to confer interests in land to third parties.

Norman Wells Proven Area Agreement

Signed in 1944 the federal government granted Imperial Oil exclusive right to drill for and produce petroleum and natural gas from the area for three consecutive 21 year terms. This agreement is valid until 2008.

Co-Operative Resource Management

A new system of co-operative resource management (co-management) was created by the Land Claim to address the longstanding concern of Sahtu people that they be provided with opportunities to participate in decisions affecting Sahtu lands. The Claim identifies three Boards responsible for resource management, including the Sahtu Land Use Planning Board, the Sahtu Land and Water Board and the Sahtu Renewable Resources Board.

The Sahtu Renewable Resources Board was the only organisation actually established through the Land Claim . The other two boards were established five years later (in 1998) through the Mackenzie Valley Resource Management Act. This Act instituted an integrated system of land and water management across regional boundaries, guided by existing land claim agreements. The Gwich'in resource management boards were also established by the act, along with the Mackenzie Valley Land and Water Board and the Mackenzie Valley Environmental Impact Review Board. As their names imply, the latter two boards are responsible for the Mackenzie Valley area including the Sahtu Region.

The purpose of the co-management system is mainly to ensure that Sahtu residents are able to participate in the management and regulation of our resources in a direct and meaningful way. The new system recognises the special knowledge that Sahtu residents have about the land, and accounts for their rights as land users and participants in decision-making. The co-management boards are accountable to the public in that aboriginal, territorial and federal governments nominate their directors. To ensure an equal voice for the rights of land claim beneficiaries, the Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated nominates one half of the members on each of the Sahtu boards.

Although the three levels of government are involved in the appointment of board members, the boards themselves are independent, and don’t directly answer to any level of government. As so-called “Institutions of Public Government,” they are accountable only to their legal mandate. This allows them to have a more direct relationship with each other, and with Sahtu residents.

The new system also involves co-operation among the boards both within the Sahtu and in bordering regions to facilitate more effective and integrated resource management. The law allows the boards to “share staff and facilities with one another for the effective and efficient conduct of their affairs.”

The Sahtu Co-Management Boards

The Sahtu Land Use Planning Board is tasked with developing a land use plan for the Sahtu that guides the conservation, utilisation, and development of the land.

The Sahtu Land and Water Board deals with water licenses and land use permits on the Sahtu. Once a Land Use Plan is in place, all licenses and permits will have to comply with the policies laid out in the plan.

The Sahtu Renewable Resources Board is the main body responsible for fisheries, forestry, and wildlife management in the Sahtu. They are guided by community-based Renewable Resource Councils.

Hertage Sites

The Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, created by the Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim, was charged with the responsibility of reviewing options and making recommendations for commemoration and protection of heritage sites in the Sahtu Region. The Working Group – representatives from the Dene and Métis people of the region, and from the territorial and federal governments – submitted its report in January 2000 to the Sahtu leadership, and to Territorial and Federal ministers.

Overview Of Sahtu Governance Structure

Figure from Draft Sahtu Land Use Plan

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: